Breaking the Cycle

by Becky Ringer

Posted on: October 3rd, 2013 by Admin

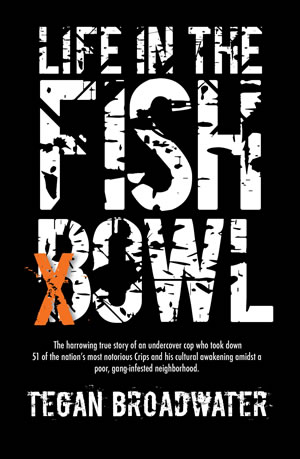

In Chapter 6 of Tegan Broadwater’s book, Life in the Fish Bowl, he described two former inner city Fort Worth drug dealers named “Li’l K” and “LA.” I label the dealers as “former” because currently they are serving time in federal prison without parole. Tegan Broadwater was an undercover officer with the Fort Worth Police Department for 13 years. He led a successful undercover drug operation in an area in Fort Worth known as “The Fish Bowl” that resulted in the arrest of 41 members of the infamous gang called the CRIPS. His recently published book tells the story and recounts details of the time he spent with specific gang members including Li’l K and LA.

Before they were arrested, Li’l K and LA, close friends and business partners, ran a successful drug business. Broadwater described Li’l K as a “smart” and “skilled street fighter” who was highly organized and rarely handled the drugs himself. As a result, he was able to avoid arrest. One of the people who saw Li’L K actually handle the drugs was LA, who often delivered and stored the illegal substances for his friend and supplier. By their business relationship, one may assert that there was a certain amount of trust between the two. This trust was about to be tested . . .

Broadwater wrote,

Though in what I can only imagine was a product of his environment and self-centered lifestyle, [Li’l] K added LA’s 14-year-old stepdaughter to his growing list of female conquests as thanks for the work LA did for him (p. 36).

As I read this passage in the book, I imagined that a huge fight was about to develop between Li’l K and LA. What is chilling, however, is that there was neither a fight nor a confrontation between LA and Li’l K. In fact, Broadwater claimed that there was no acknowledgment of the act from LA or any of the gang members who worked with them. Broadwater noted that

[the] power [Li’l] K wielded combined with the need to keep money flowing in the Fish Bowl far outweighed the need for someone to step up in defense of some expendable 14-year-old. The sad truth is that the cycle continues to grow, claiming new victims like LA’s stepdaughter every day in hoods and suburbs alike. The cycle stops only when the perps are locked away (p. 36).

The disregard that these gang members had for this 14-year old girl took my breath away. It is the same disregard that the gang members had toward the children often born out of such acts. Broadwater wrote

I had one person in this operation tell me his girl was pregnant literally one day before the due date. I was congratulatory and excited for him, yet he responded in a business-like way; explaining he wouldn’t be at the hospital to witness the birth and was not sure if they would be “moving in” together or not.

In another instance, I was interviewing Aaron, an arrestee from Operation Fish Bowl who had a very hard time recalling the names of his last three children—all of whom were born within the past year and a half by different mothers (p. 153).

To these fathers, their children are nameless and faceless and not even an inconvenience. To be inconvenienced by their children, these fathers would have to actually acknowledge them. To these fathers, the babies are less significant than a piece of trash that is tossed away.

As we know, these children do have names and faces. These children have feelings. If given the chance, these children have hopes and dreams. Part of the cycle is broken, as Broadwater states, “when the perps are locked away.” However, the other part of the cycle that has to be addressed is the children who are left behind after their fathers and mothers are locked away. Their inevitable search for adult role models may result in a dangerous situation if the right role models are not ready to lead.

At the end of his book, Broadwater offers a solution to the ongoing cycle of today’s fatherless children becoming tomorrow’s highly dangerous criminals. He states that

[t]here needs to be proper and specific education in place for children with incarcerated parents at a young age. They need to be encouraged and mentored. They must learn to be accountable and fight against economic and societal odds. They must learn to properly love and to love God (p. 154).

There are two levels of interest in Tegan Broadwater’s book, Life in the Fish Bowl. On the surface, it is a good read about how a white undercover police officer was able to gain access to such a tightly secure network of gang dealings in the inner city of Fort Worth. His ability to stay relaxed and know how to play the game saved his life more than once.

On a deeper level, however, this book is important because it is a call to action. We have a crisis in our own city of Fort Worth that was certainly slowed down by Broadwater’s operation after he arrested the 41 gang members. The crisis is not over, however, and the children, who were born before, during, and after this operation, need our attention. These children want to be acknowledged and given a chance to hope and dream. I wonder if Tegan Broadwater anticipated how deeply his heart would be moved and changed after his work in the Fish Bowl. As he began to write, I wonder if he realized that he would make such an important call to action when he told his story.

Part of the proceeds of Tegan Broadwater’s Life in the Fishbowl is being donated to H.O.P.E. Farm. To learn more about H.O.P.E. Farm, a ministry for fatherless, at-risk boys in the inner city of Fort Worth, visit www.hopefarminc.org. To learn more about Tegan Broadwater and his work, visit www.fishbowl41.com